Esophageal cancer background

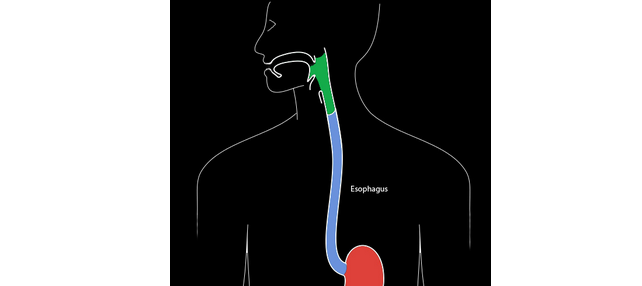

The esophagus (blue in figure) is a muscular tube that carries food from the back of the mouth (pharynx – green) to the stomach (red) (figure 1). Cancers that occur in this organ are often difficult to treat, in part because “alarm symptoms” such as difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) or bleeding often do not appear until the cancer is at a late stage. Unfortunately, less than half of persons with esophageal cancer survive more than a year after diagnosis. Therefore, preventing this cancer and detecting it at an early stage remain the most effective options for reducing mortality from the disease.

Cancers arising in the esophagus are typically classified as one of two histologic types. The lining of the esophagus normally consists of squamous cells, which can give rise to a type of cancer - esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) - occurring anywhere in the esophagus. Sometimes a portion of the esophagus becomes lined with columnar cells, which are similar to the lining of the small intestine, in a process termed metaplasia. This usually occurs under conditions of chronic gastroesophageal reflux (e.g., heartburn or acid regurgitation) and the resulting condition is termed Barrett’s esophagus, which is a precursor to the second type of cancer – esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). EACs usually arises in the lower third of the esophagus or at the junction with the stomach (gastroesophageal junction.)

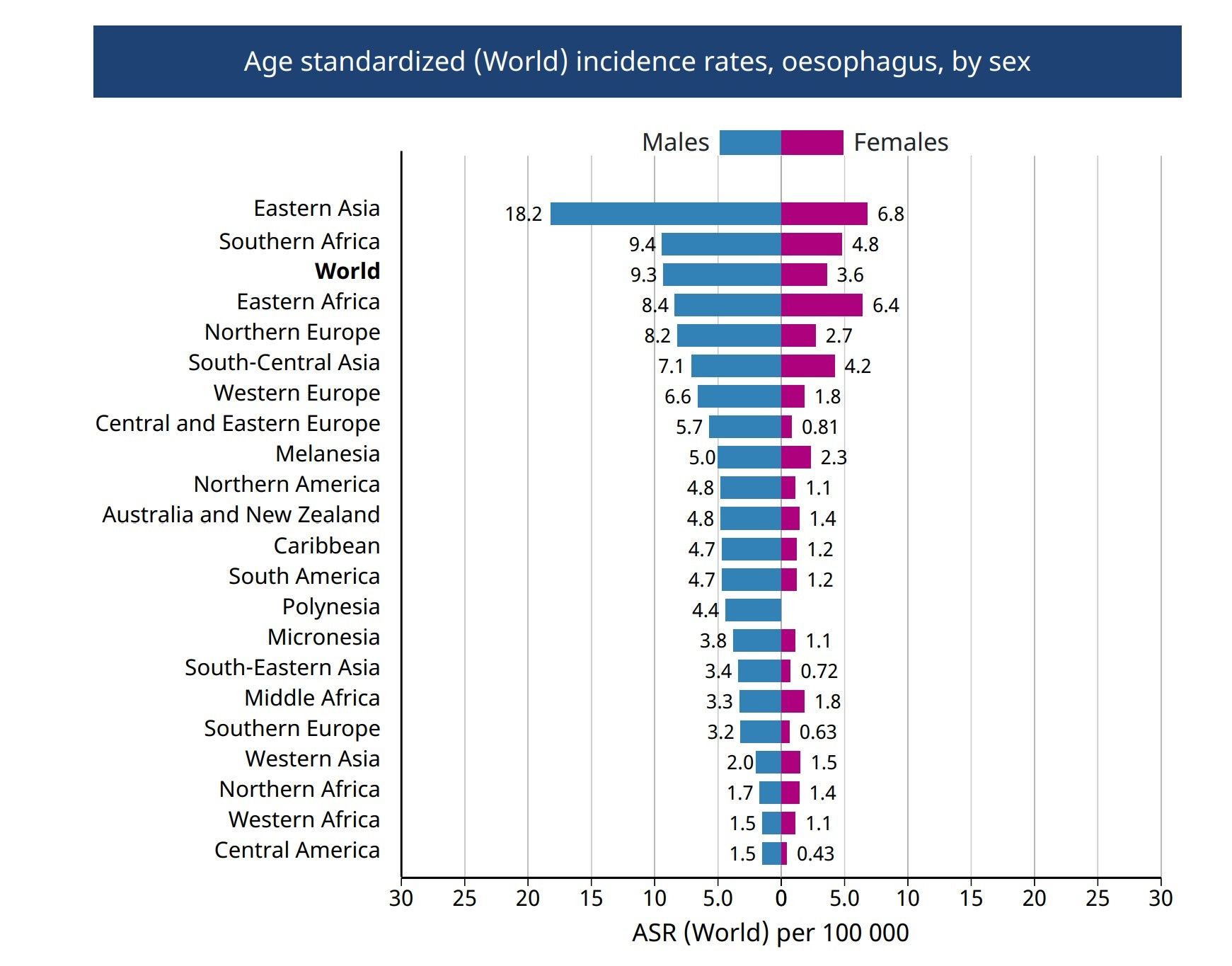

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) estimates that 604,100 new cases of esophageal cancer occurred worldwide in 2020, making it the seventh most commonly occurring cancer and the sixth most common cause of cancer death.(1) Of these cases, an estimated 15% were EAC, 84% ESCC and the remainder rare histologic types.(2) Esophageal cancer of both types generally occurs more often in men than in women, although the ratio varies substantially by country (figure 3).(1)

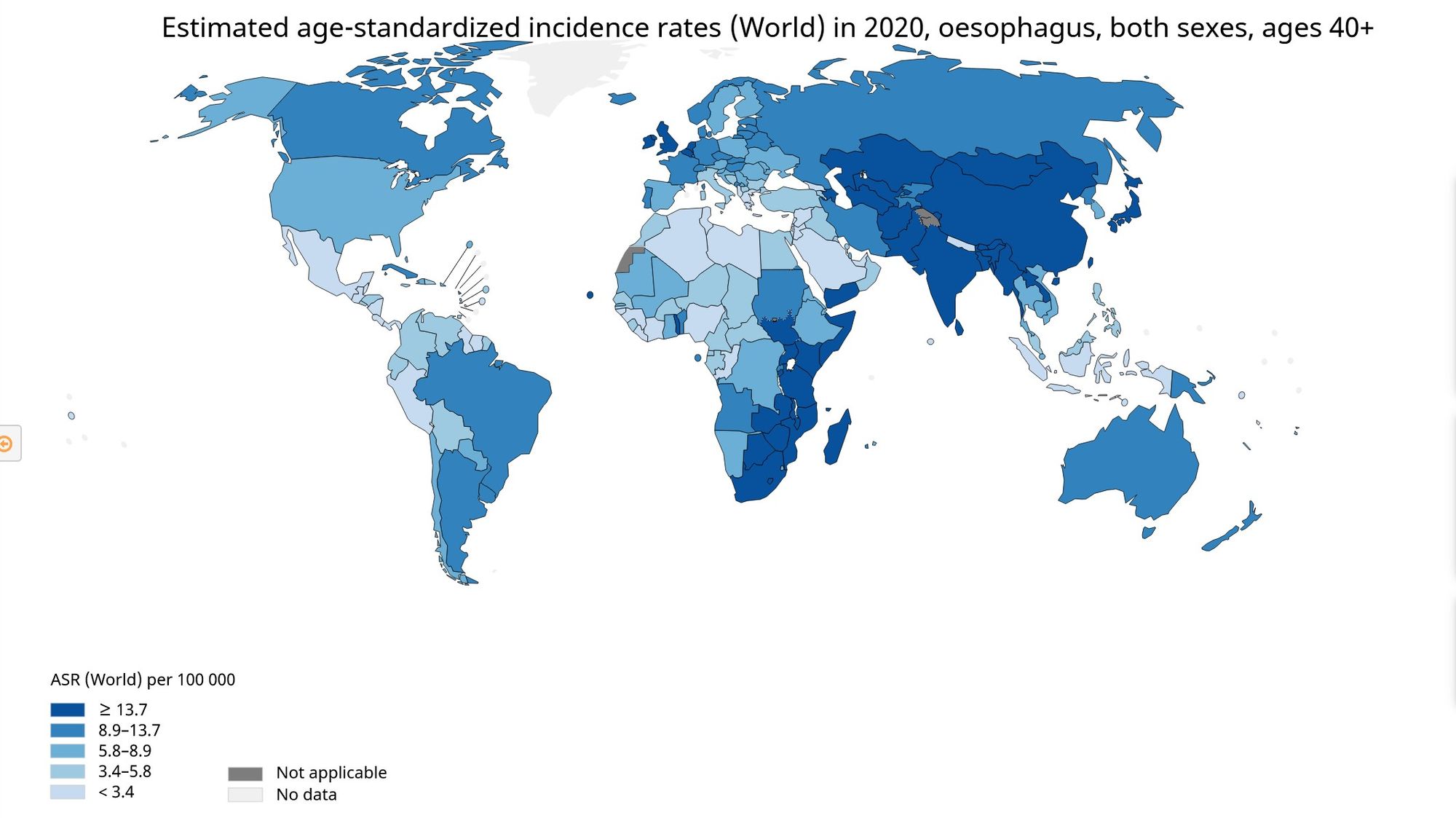

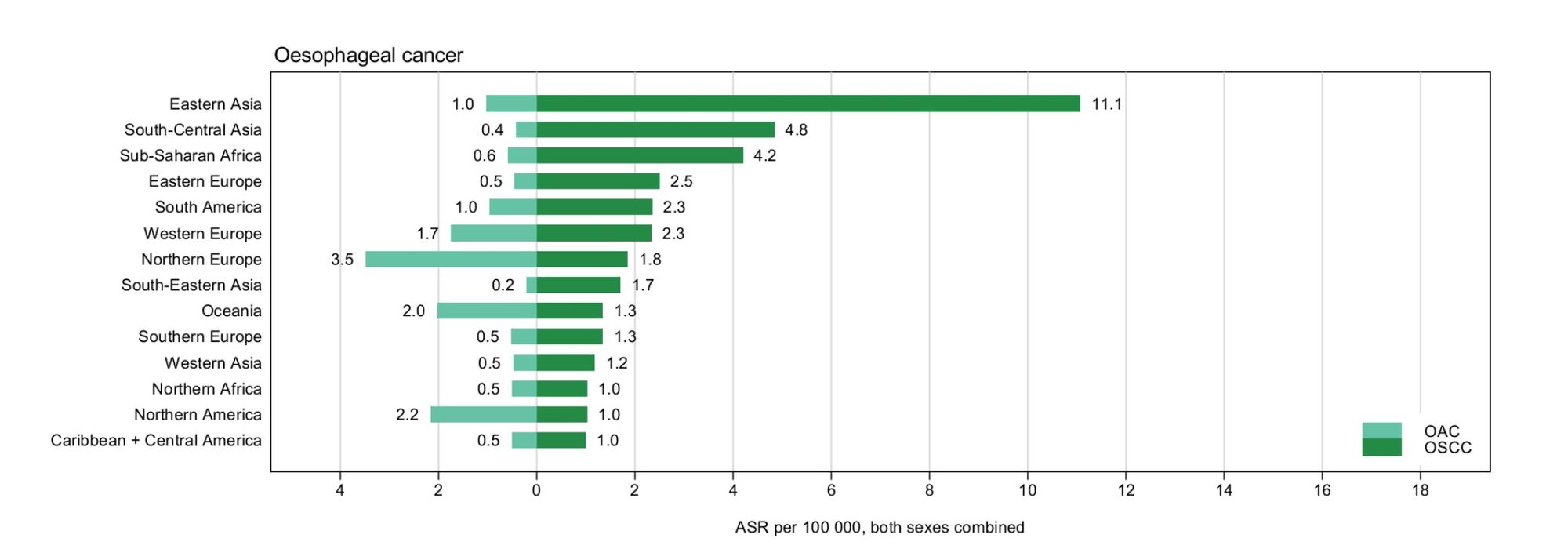

In less developed regions, ESCC is by far the most common histological type. Particularly high rates occur in parts of China, Central Asia and Eastern Africa (figure 2.) In contrast, the United States and much of Western Europe and Australia has seen a remarkable rise in the incidence of EAC which has transformed it from a relative rarity in the 1970s to the most common histological type of esophageal cancer in the U.S. today.(3-6) The age-standardized incidence rates of EAC and ESCC by world region are summarized in Figure 4 (2).

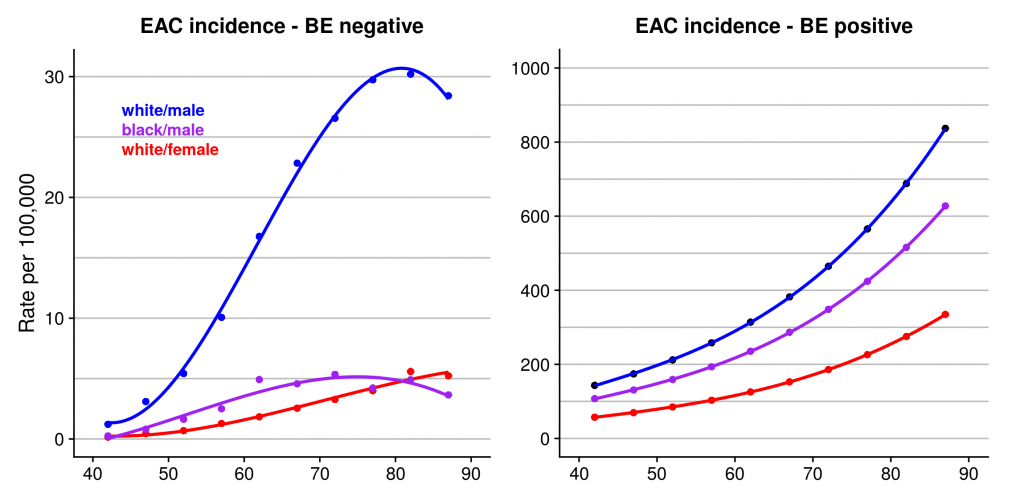

EAC is particularly common among white males, in whom incidence has increased about 10-fold in the U.S. since the early 1970s.(7) Incidence rates in other groups also have risen, although from a much lower baseline rate. Like many solid tumors, EAC incidence rises rapidly with age (figure 5, left graph.) Persons diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus are substantially more likely (about 20-fold at 60 years of age) to develop EAC than the general population (figure 5, right graph.)(8)

Both absolute incidence rates and time trends vary considerably by world region and by country within regions (figure 6) (9). Among the countries with longer-term cancer registries, including the U.S., Canada, Australia and Scotland, EAC became the most common type in white males all at about the same time - the mid 1990s. In contrast, this "crossing of the lines" is occurring about 20 years later among white females. Incidence of ESCC among males has generally declined in most regions of the world, whereas incidence among females has been stable or even increased in some regions.(10)

References:

1. Cancer today. Available at: http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. (Accessed: 22nd April 2021)

2. Arnold M, Ferlay J, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Soerjomataram I. Global burden of oesophageal and gastric cancer by histology and subsite in 2018. Gut. Sep;69(9):1564–71 (2020).

3. Hur, C. et al. Trends in esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality. Cancer. 119, 1149–58 (2013).

4. Islami, F., DeSantis, C. E. & Jemal, A. Incidence Trends of Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Subtypes by Race, Ethnicity, and Age in the United States, 1997-2014. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (2018). doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2018.05.044

5. Malhotra, G. K. et al. Global trends in esophageal cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 115, 564–579 (2017).

6. Xie, S.-H. & Lagergren, J. Risk factors for oesophageal cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. (2018). doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2018.11.008

7. Vaughan, T. L. & Fitzgerald, R. C. Precision prevention of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 243–248 (2015).

8. Anon. IC-RISC. Available at: [https://ic-risc.esocan.org/

9. Thrift AP. Global burden and epidemiology of Barrett oesophagus and oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2021) Feb 18.

10. Wang Q-L, Xie S-H, Wahlin K & Lagergren J. Global time trends in the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:717–28.